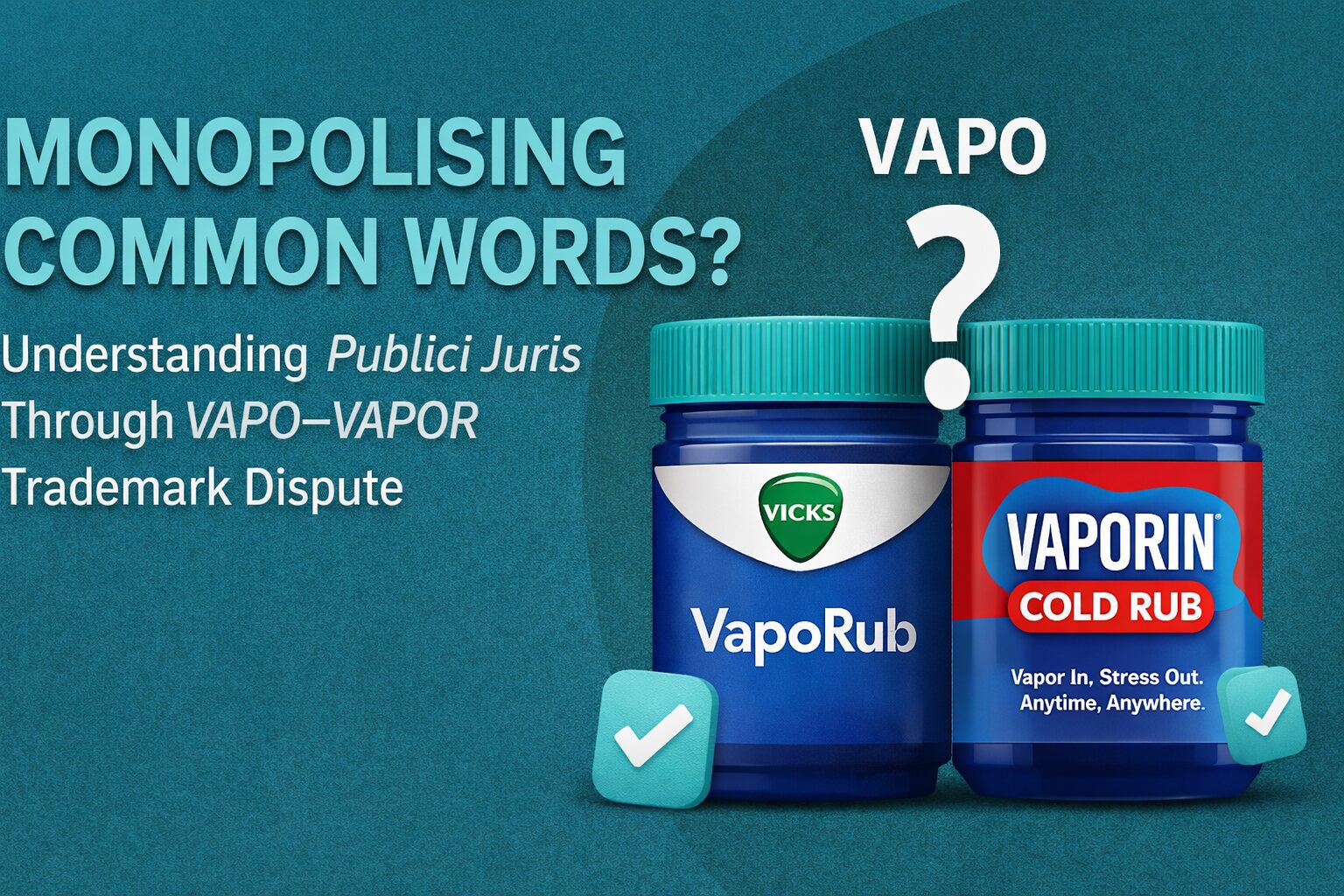

In trademark law, exclusivity is not absolute. Courts have consistently held that no trader can monopolise words that have entered the public domain. A recent judgment [Madras High Court order dated January 6, 2026 in The Procter and Gamble Company Vs IPI India Private Limited ( O.P.(TM)Nos.48, 49 and 50 of 2024) ] dealing with the use of the term “VAPO / VAPOR” once again reaffirms this fundamental principle, drawing a clear distinction between brand protection and public right to use generic expressions.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Core Issue: Can “VAPO” Be Exclusively Claimed?

The dispute arose when the petitioner, proprietor of the well-known product “VICKS VAPORUB”, objected to the use of the expressions:

“Vapor In, Stress Out. Anytime, Anywhere”

“VAPORIN COLD RUB”

“VAPORIN”

by the first respondent.

The petitioner contended that the respondent’s marks were deceptively similar and likely to cause confusion among consumers. The court, however, rejected this contention and placed decisive emphasis on the doctrine of publici juris.

“VAPO” and “VAPOR” as Publici Juris

The Court held that the term “VAPO” (derived from “vapor”) is a descriptive expression commonly associated with vapour-based or inhalation products. Such words, by their very nature, belong to the public domain.

Once a word becomes publici juris:

No single entity can claim exclusive proprietary rights over it.

Its use by another trader does not automatically amount to infringement.

Trademark protection extends only to the mark as a whole, not to common or descriptive elements.

The Court categorically observed that nobody can claim an exclusive right over an abbreviation or expression that has become publici juris.

Phonetic and Visual Dissimilarity Matters

Another crucial aspect examined by the Court was deceptive similarity, both phonetic and visual.

The Court found that:

“VICKS VAPORUB” and “VAPORIN” are phonetically dissimilar

The overall visual appearance, get-up, and structure of the marks are completely different

The respondent’s products carry distinct branding and presentation

In trademark infringement analysis, similarity must be assessed holistically, not by isolating a common word. Merely sharing a descriptive term like “VAPO” or “VAPOR” is insufficient to establish confusion.

No Likelihood of Consumer Confusion

The Court further held that:

An average consumer, exercising ordinary prudence, would not confuse the petitioner’s product with that of the respondent.

The products are distinct and identifiable, despite both operating in a similar therapeutic space.

The presence of different prefixes, suffixes, and branding elements significantly reduces any likelihood of deception.

Accordingly, the rival marks were held to be neither identical nor deceptively similar.

Key Legal Principles Reaffirmed

This judgment reinforces several settled principles of trademark law:

Descriptive and generic words cannot be monopolised

Publici juris terms remain free for all traders to use

Trademark protection lies in the overall impression of the mark

Phonetic and visual differences are decisive in infringement analysis

Well-known marks do not enjoy blanket protection over common words

Conclusion

The ruling draws a careful and much-needed balance between protecting brand identity and preserving free use of language in commerce. While trademarks serve as source identifiers, they cannot be stretched to suppress legitimate use of descriptive or commonly used expressions.

By holding that the use of the term “VAPO” does not render the respondent’s mark deceptively similar to “VICKS VAPORUB”, the Court has reaffirmed that trademark law protects distinctiveness—not dominance over public vocabulary.