Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

In Criminal Appeal arising out of SLP (Crl.) Nos. 11530 & 14783 of 2024, Yerram Vijay Kumar vs. State of Telangana , decided on 9 January 2026, the Supreme Court delivered an authoritative ruling on the interplay between Sections 447, 448, 451, 212(6), and 436 of the Companies Act, 2013, and the extent to which private criminal complaints can be entertained for alleged corporate fraud .

The judgment has far-reaching implications for corporate governance, shareholder disputes, director liability, and the jurisdiction of Special Courts under the Companies Act.

Factual Context: Corporate Control Dispute Escalating into Criminal Prosecution

The dispute arose from the internal affairs of a private limited company, involving:

amendments to Articles of Association (AoA),

alleged illegal convening of EOGMs,

disputed appointment of directors, and

filing of statutory forms (including DIR-12) with the Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

While company law remedies were already invoked before the NCLT under the Companies Act, a private criminal complaint was simultaneously filed before the Special Court for Economic Offences, leading to cognizance under:

Sections 448 and 451 of the Companies Act, and

various provisions of the IPC.

The central question before the Supreme Court was whether such cognizance was statutorily permissible.

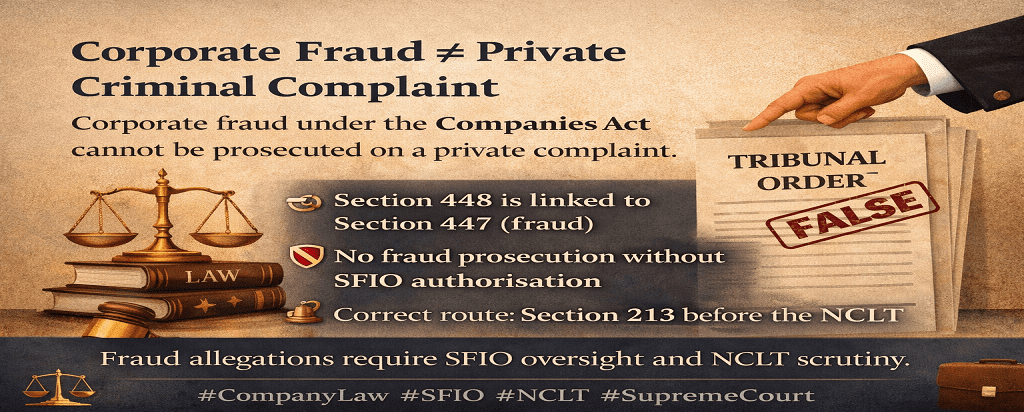

Section 448 Read with Section 447: Fraud as a Statutory Construct

A key contribution of the judgment lies in its clarification of the legal architecture of Section 448.

Section 448 does not prescribe an independent punishment.

It expressly provides that a person making a false statement in statutory filings “shall be liable under Section 447”.

Section 447 is the substantive punishment provision for fraud, with stringent penal consequences.

The Court held that Section 448 cannot be read in isolation. Any prosecution under Section 448 is, in substance and in law, a prosecution for fraud under Section 447.

Result: An offence under Section 448 is an “offence covered under Section 447” for the purposes of the Companies Act.

Section 212(6): Mandatory Bar on Cognizance of Fraud Offences

The Court gave a strict and purposive interpretation to the second proviso to Section 212(6), which provides that:

No court shall take cognizance of an offence covered under Section 447 except upon a complaint in writing by the Director, SFIO or an authorised officer of the Central Government.

Key Findings

The bar under Section 212(6) is not procedural but jurisdictional.

Allowing private complaints for Section 448 offences would defeat the statutory safeguard built into the Companies Act.

The legislature intentionally channelled fraud prosecutions through SFIO / Central Government oversight to prevent misuse by disgruntled shareholders or rival factions.

Accordingly, the Special Court lacked jurisdiction to take cognizance under Sections 448 and 451 on a private complaint.

Section 451 (Repeated Default): Dependent on Valid Primary Offence

Section 451 penalises repeated commission of an offence under the Act. The Court held that:

When cognizance of the primary offence (Section 448) itself is barred,

Cognizance of Section 451 automatically collapses.

Thus, prosecution under Section 451 cannot survive independently.

Section 213 as the Proper Remedy for Alleged Corporate Fraud

Importantly, the Court clarified that complainants are not remediless.

Where allegations involve:

fraud in management,

falsification of corporate records,

abuse of control,

the statutorily sanctioned route is:

an application under Section 213 of the Companies Act before the NCLT, seeking investigation,

which may then culminate in SFIO action and prosecution, if warranted.

This preserves the regulatory hierarchy and investigative discipline envisaged by the Act.

Section 436(2): Jurisdiction of Special Courts and IPC Offences

While quashing proceedings under the Companies Act, the Court made a crucial distinction:

Section 436(2) allows a Special Court to try IPC offences only when it is also trying offences under the Companies Act.

Once Companies Act offences are quashed, IPC offences must be tried by the regular court of territorial jurisdiction.

Accordingly, the Court directed transfer of the IPC case to the appropriate criminal court, while allowing those proceedings to continue independently.

Corporate Law Significance of the Judgment

Key Takeaways

Fraud under company law is a regulated offence, not open to private criminalisation.

Sections 447, 448, and 212(6) form a composite statutory scheme.

Special Courts cannot bypass SFIO-centric safeguards by entertaining private complaints.

Corporate disputes cannot be converted into criminal fraud cases without following the Companies Act’s investigative framework.

NCLT remains the primary forum for corporate governance and control disputes.

Conclusion

This judgment decisively reinforces the principle that company law is a self-contained, statute-driven code, especially in matters of fraud. By insisting on strict compliance with Sections 212, 213, and 447, the Supreme Court has strengthened:

corporate certainty,

regulatory discipline, and

protection against abuse of criminal process in shareholder and boardroom disputes.

For corporate advisors, directors, and litigators, the ruling is a clear reminder that criminal liability under the Companies Act arises only through statutorily sanctioned channels—and not by private shortcut